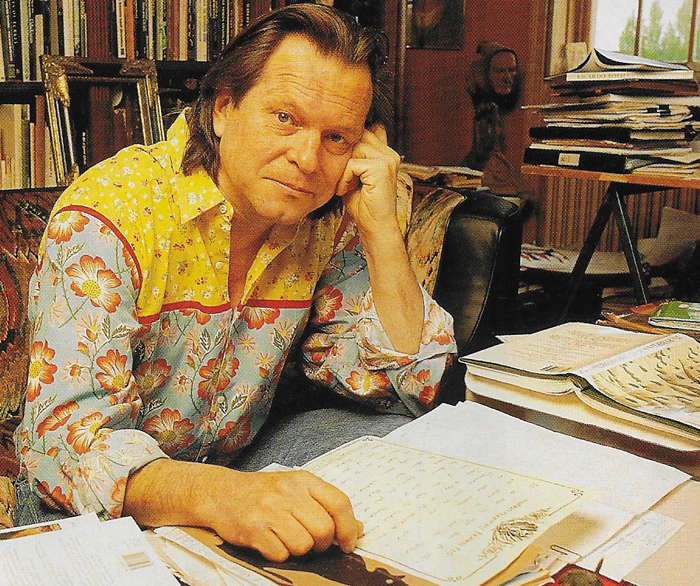

“What has always intrigued me about Don Quixote,” says Terry Gilliam, “is that he is a dreamer, an idealist, a romantic. He is determined not to accept the limitations of reality. It’s a very noble cause, yet he always manages somehow to keep marching on.”2

Some people may reasonably argue that the last few sentences also describe Gilliam’s own quest to make a film of Don Quixote. The director started work on the project in 1989, and despite many obstacles, his picture The Man Who Killed Don Quixote is now complete, and it was rewarded with the coveted closing night slot of the 2018 Cannes Film Festival.

Now that Gilliam has finally completed his Quixote dream project, here we look back at the early years of the director’s own noble cause. We look back 29 years to 1989, where our story begins. This is when Gilliam first came up with his irrational notion to make a film about the Knight of Doleful Countenance.

***

In 1989, as The Adventures of Baron Munchausen4 was released around the world5, Terry Gilliam was seeking his next project. He spent some time on a version of Fungus the Bogeyman, working with Terry Jones and Neil Innes6. He also had been working on a film adaptation of Alan Moore’s graphic novel Watchmen7, yet despite the best efforts of Gilliam and producer Joel Silver, they were unable to finance it.

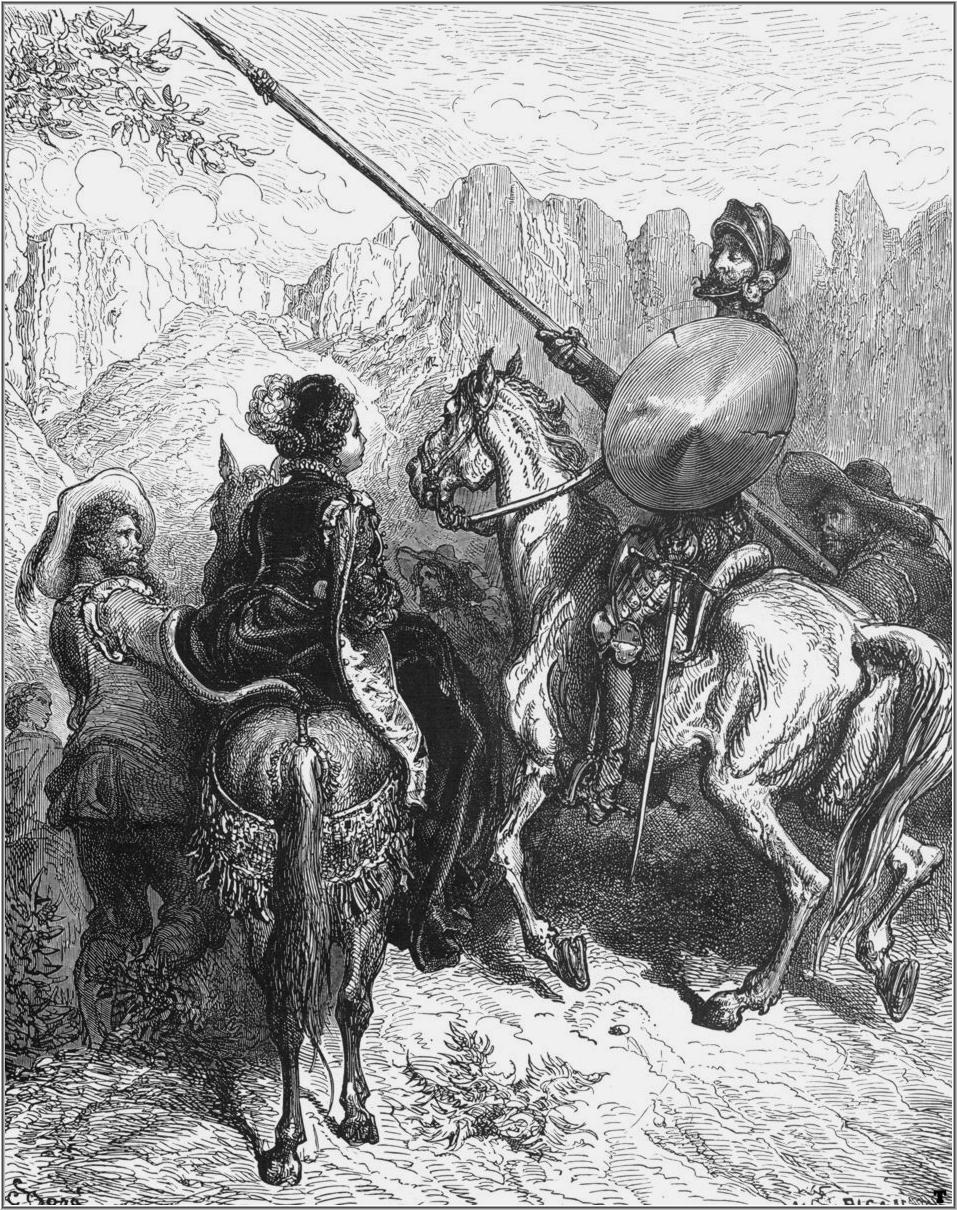

At the time, Gilliam was becoming enchanted with the character of Don Quixote – the filmmaker having completed a number of films which championed imagination and madness over the dull consequences of accepting reality. Gustave Doré played a part in this, having illustrated a Munchausen book in 1866, and having also done the same for Don Quixote a few years earlier in 18638.

Gilliam’s first attempt9 to get funding for Quixote was straightforward. He contacted his pal Jake Eberts, a Canadian who had been the executive producer on Munchausen. Gilliam recalls, “We both were keen to do something else together, and one day I called him and said, ‘Jake, I’ve got two names for you – one is Quixote, the other is Gilliam, and I need 20 million dollars.’ And Jake said ‘Done’. It was as simple as that.”10

With the offer of funding, Gilliam was faced with his first challenge11, “I hadn’t actually read the book, and like most people, I only knew a vague outline of what Quixote is and what he stands for. So I started reading the book, and the complications began. Several weeks later, I finished reading the book, and said to myself, ‘Jesus, this is unfilmable!’ I realised that I couldn’t make the film. How could I begin to write a script that is broad, long and intricate as those books?”12

The novel Don Quixote was written by Miguel de Cervantes in the early 17th century. Its full title is The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha, and it was published in two volumes, the first in 1605, and the second in 1612. Its appeal to Gilliam is strong. “I think most people understand what he’s about – a man who is the victim of reading romantic novels of chivalry, of knighthood, of King Arthur. His brain is inflamed by these images and ideas of knightly conduct. He sets out to have his adventures, to make his name in the world of knight errantry and of course he’s constantly coming up against reality which he totally misinterprets – for example thinking sheep are warring armies, thinking windmills are giants. And he marches on and he’s constantly crushed, smashed back by reality. Yet he marches on.”13

Yet despite the problems he’d identified in adapting the text, Gilliam began the work writing a script with Charles McKeown, with whom he had written Brazil14 and Munchausen. McKeown recalls working for about a year in 1989 and 1990, trying to remain faithful to the original text. McKeown says, “I can’t remember exactly how long we spent writing but it was at least a year. The idea we had was to stick to Cervantes’s book, yet do it in a way that hadn’t been done before.”15

McKeown recalls their method of working as follows, “We’d meet together, talking about everything except the movie, then finally getting down, talking about ideas for the movie: what he wanted and any ideas I had as well. After several days of that, sketching things out, me making notes, I would go and write some scenes and bring it back to him. He would look at that and say what he liked about it and what he didn’t like about it. And I would then go back and work on that and at the same time we would be discussing the next stage.”16

Over that time period a full first draft script was completed. McKeown recalls that Cervantes’s Cardenio storyline detours were axed from their adaptation, but, “there’s certain things you have to have, and we might have ended up with a script not very dissimilar to what everyone else had.”17

Now while Gilliam was working on his visualization of Quixote, with the $20 million funding looking solid, he received what appeared to be a better offer. “I was hot at the time, and a French company called Ciby 200018 said they would give me $25 million.” So Gilliam went to see Eberts, who had now moved to an office in Paris. Gilliam said to the producer, “They are offering me 25, what do you think? I think we need that much money, having read the book and having worked on the script.” Eberts told the filmmaker to grab the better offer. “So I walked across the Champs Élysées to Ciby 2000,” says Gilliam.19

Work continued on Quixote with a slightly higher budget, and Gilliam set his mind to casting decisions. “Sean Connery was mooted,” recalls the director, “but Quixote is air and Sean is earth, so I backed away. I saw Nigel Hawthorne as Quixote and Danny DeVito as Sancho Panza.”20

The director also went location scouting in Spain, and found himself following in Ridley Scott’s footsteps, eyeing up places used to make 1492. “Ridley’s got a good eye, so we ended up looking at the same places.” said Gilliam.21

During this period of writing and scouting, Gilliam bumped into Richard Lester, one of his key influences, and a filmmaker who himself is a long-time aficionado of the Sad Knight. In fact, Lester has been fascinated by how different scripts22 have tackled what he sees as the central problem of making a film about Quixote. Lester gave Gilliam a friendly warning.

Says Lester, “I have always said that there are three works that should never ever be made on film, all for the reason that they will never, ever work. I recall saying this to Terry. One of them is Candide, a great story, the second is Baron Munchausen, and the third is Don Quixote. And with unerring accuracy, Terry leaps towards these projects. I have lived on and off in Spain since 1954, and I have made seven films in Spain; I adore the country. And I have been sent probably every decent Quixote screenplay ever written over the years, including the one by Waldo Salt23. I keep them because I’m always fascinated by them.24

“My take is that when you have a hero of a film that is mad,” added Lester, “the audience cannot see the structure of where the story is going, because your leading character is not defining the story. Quixote can fight the windmills in reel one, or you could put it in reel nine – it wouldn’t make any difference. There’s no connection with what’s going on because he is mad. And I think a leading character has to connect with the scenes that propel the story along, otherwise the audience gets turned off.”25

In 1990, Gilliam found that his $25m funding offer for Quixote was insecure. He remembers, “A year or so later, we were going around in circles. Nothing was coming together. Suddenly, the money from Ciby 2000 wasn’t solid. I’d given up on a sure thing, and taken the more beautiful apple, and then we were languishing. Nevertheless, we’d started.”26

But money was not the only difficulty with the project. The director was unsatisfied with how the script had developed, and creative differences were emerging with his co-screenwriter McKeown, who recalls, “We’d got a first draft, and obviously it was going to need a lot more work on it. But at that point I think Terry thought it was a bit boring following this particular line, and in hindsight he was probably right. He felt it wasn’t interesting enough, yet I wanted to persevere along the same line. He wanted to strike out in another direction and do something a bit more different with it, and bring it up to date and give it a modern setting, and I wasn’t really ready for that.”27

He also suggests further concerns about problems inherent in the novel, echoing the advice that Lester had given. McKeown says, “We found the problem with the book, and with the script that we had, is that Don Quixote himself is essentially a passive character. Things happen to him. He doesn’t really make things happen; they happen around him. In terms of narrative, he’s not a big driver of the story. And that as I recall presented something of a problem.”28

So Quixote momentum reduced to zero, and Watchmen and Fungus were unable to provide work for Gilliam by early 1990. Instead, Gilliam’s attention was grabbed by a script sent to him on spec: The Fisher King, by Richard LaGravenese. The script had remarkably strong connections with Quixote, as disturbed Parry (Robin Williams) inspires selfish Jack (Jeff Bridges) on a quest.

Shooting took place in the summer of 1990, on location in New York City and in the studios in Los Angeles. Postproduction lasted into 1991, and the picture was released in September of that year. The Fisher King was a hugely popular film, scoring the top spot at the US box office for three weeks29. It went on to Oscar success.

The critical and financial success of this picture emboldened Gilliam. With this behind him, he concluded that he would find it easy to get another film into production. But this was not the case: he had a three-year wait until another movie received a green light.

Gilliam threw himself into a number of varying projects after The Fisher King, but these came and went. With LaGravenese he not only created an original script, The Defective Detective, but also collaborated on an adaption of Philip K Dick’s A Scanner Darkly. The former gathered significant interest, and development funding from Scott Rudin at Paramount, but never gained a green light. Gilliam made significant attempts at A Connecticut Yankee in King’s Arthur’s Court, A Tale of Two Cities, and The Hunchback of Notre Dame. He also seriously considered a live action/animation combo script called Looney Tunes, and also a film about Nikola Tesla.30

The director’s admirers were not reassured in January 1994 when he appeared in an Empire magazine article called “Development Hell”, looking rather glum. He talked about many potential feature films, yet Quixote was not mentioned. Gilliam said, “I hope to get a couple more films done before I die.”31

Finally, in 1994, Gilliam was given a directing opportunity with funding attached. It was an offer from Universal to direct Twelve Monkeys. Starring Bruce Willis, Madeleine Stowe and Brad Pitt, the shoot lasted from February to May 1995, with postproduction lasting until the end of the year. It hit the screens at the end of December 1995.

Again, those looking for Quixote-like resonances were not disappointed, though maybe not quite as strong as in The Fisher King. Until the end of the film, there was ambiguity whether Cole was indeed mad or a time traveller.

There was little mention of Quixote in interviews supporting the Twelve Monkeys release. In one interview32, Don Quixote gets a very brief mention, “I’m working on doing Don Quixote. It’s not my story, but it’s my adaptation.” In another33, Gilliam said Quixote was “still in the works. The script marches on, but not to anyone’s satisfaction yet.”

Around this time, it was announced that Fred Schepisi was to direct a version of Quixote with John Cleese and Robin Williams, using the Waldo Salt script, with US producer Elisabeth Robinson. Said Gilliam at the time, “That really hurts, that I let a project I’m convinced I’m the best director on the planet to do, slip by.”34 Yet the Schepisi film fell apart early in 1997 when it was “well into pre-production.”35

Announced during the production of Twelve Monkeys was The Crowded Room36, a feature film based on the multiple-personality defence of Billy Milligan. Brad Pitt was attached but it came to nothing.37 The director was also keen for a while on adapting Larry McMurtry’s Anything for Billy for screen. Gilliam was also still keen to direct his pet project The Defective Detective, but still no green light was attained. In March 1997 it had been rumoured that Gilliam was ‘firmly attached’ to Manhattan Ghost Story, a Ron Bass script based on the novel by T.M. Wright. In the end Gilliam turned it down.

At this time, Gilliam returned to a project that he has wanted to do since the late 1970s, based on Theseus and the Minotaur. For help now, he contacted screenwriter Tony Grisoni, whose magical London-based script The Lives of the Saints had impressed Gilliam a few years earlier.38

All of this was put on hold when Gilliam was offered the opportunity to direct Hunter S. Thompson’s Fear & Loathing in Las Vegas, when the gonzo journalist had a row with the then-attached director Alex Cox. Gilliam entered the project in April 1997, then in May spent a short and intense period39 writing the script with Grisoni. Johnny Depp40 and Benicio del Toro were already committed, and Gilliam’s involvement enabled a budget increase, with funding from Universal.

The Summer 1997 shoot took place on location in and around Las Vegas, and studio work followed in Los Angeles followed. Postproduction lasted until early 1998, and then in May of that year the picture was premiered in competition at the Cannes Film Festival. Gilliam enjoyed working with Depp, and said, “It’s amazing to watch him work. I quite like him going as far as he can, physically, and still hold on to [his character].”41

Don Quixote had kept a low profile in Gilliam’s mind since 1991, yet it was relaunched during the postproduction of Fear & Loathing. In late 1997, Gilliam was considering two projects as his next film: The Defective Detective and Don Quixote. Gilliam said, “Quixote has just floated around. I’ve never felt we’d got the script right; it’s a very complex project to get right. It’s a bit like a painter who’s got several canvasses going at once. You walk away from it for a bit and don’t look at it. And you look back at it and you begin to see what’s right and what’s wrong. And Quixote is one we haven’t got right yet.”42

This is probably the last time that Gilliam could have walked away from the idea of making a film about Don Quixote. His last three films had contained Quixotic elements, yet Gilliam still hadn’t purged himself of the enchantment that had first overcome him in 1989.

Gilliam didn’t walk away. He was about to make a major breakthrough in his desire to tell the story of the Sad Knight to a contemporary audience. By this time he was hooked. “There’s no-one I can blame,” Gilliam sighs, “It’s the danger of books. I unfortunately like reading, and that’s where the addiction begins!”43

In the next instalment, we learn how Gilliam developed The Man Who Killed Don Quixote with Tony Grisoni; how a 1999 attempt collapsed; and how further challenges were faced raising the funds for the 2000 shoot.

Phil Stubbs has followed Terry Gilliam’s Quixote project closely since its beginnings in 1998. While visiting the Quixote set in 2017, he suffered an injury and broke three bones.

1. Author Interview, February 2016

2. AI, February 2016

3. Text containing this footnote was deleted since it was obsolete

4. Postproduction was completed ready for its West Germany release in December 1988, with other territories releasing the picture from March 1989.

5. with varying levels of box-office success

6. See Gilliam on Gilliam, ed. Ian Christie, faber & faber for further information

7. in fact he wore a blood-stained smiley badge while publicising Munchausen in March 1989.

8. Dates from Wikipedia page on Gustave Doré (1832-1883). Hopefully they are correct.

9. of many

10. AI, February 2016

11. of many

12. Gilliam has told this story slightly differently to several journalists over the years. This version is a combination of AI, February 2016, with a detail added from Sean O’Hagan, The Observer, 4 February 2001.

13. AI, February 2016

14. Also with Tom Stoppard of course

15. AI, August 2016

16. AI, August 2016

17. AI, August 2016

18. Pronounced “C. B. de Mille”, it was a French production outfit responsible for four Palme D’Or winners.

19. All this detail from AI, February 2016

20. Neon magazine, “Terry Gilliam’s 10 movies they wouldn’t let me make”, March 1997

21. Dark Knights and Holy Fools, Bob McCabe, 1998.

22. largely unfilmed

23. Blacklisted American screenwriter responsible for Midnight Cowboy, Serpico and Coming Home

24. AI, July 2002. Lester pointed to a pile of scripts gathering dust in his office.

25. AI, July 2002

26. AI, February 2016

27. AI, February 2016

28. AI, February 2016

29. From Box Office Mojo

30. Read Dark Knights and Holy Fools by Bob McCabe for more information on these

31. “Development Hell”, by Matt Mueller, in Empire January 1994

32. A brief mention in a mammoth 29-page interview by Paul Wardle in the November 1995 issue of The Comics Journal.

33. Gilliam talking to MJ Simpson of SFX magazine, February 1996

34. Neon magazine, “Terry Gilliam’s 10 movies they wouldn’t let me make”, March 1997

35. See the following website for more information: Senses of Cinema

36. Cosmopolitan, early 1997

37. now the project has moved forward with Leonardo DiCaprio

38. From “Stalking Red Riding Hood” by David Gritten, available at Blue Toad

39. Lasting eight days

40. More on him later

41. Gilliam talking at the UK premiere of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, at Dreams Fanzine at Edinburgh Festival

42. AI, December 1997

43. AI, February 2016