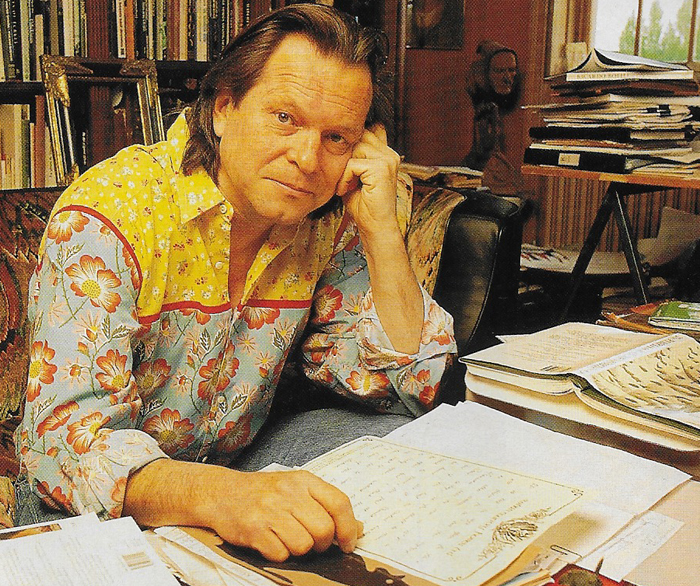

Fortune is smiling on Terry Gilliam, reports Phil Stubbs from the set of the director’s macabre new film. Gilliam photography by Phil Stubbs.

TERRY GILLIAM gleefully punches a fake cadaver’s face to make it look more damaged. He’s working inside a four-walled bedroom set where three actors and the corpse are about to perform another take. There’s little enough room for the actors, never mind the director, the cinematographer and the camera.

Having exhibited a predilection for the grotesque throughout his career, the former Python is now shooting Tideland, an adaptation of Mitch Cullin’s surreal Southern Gothic novel, with Jeff Bridges. The director describes the project as “Psycho meets Alice in Wonderland.” The story follows Jeliza-Rose, a feisty ten-year-old who escapes with Noah, her waning rock-star father, to Texan prairie-land after her groupie mother dies from an overdose. She meets bizarre neighbours: a middle-aged woman, Dell and her brain-damaged younger brother, Dickens. But Jeliza-Rose’s closest confidants are doll’s-heads, each of which she gives a distinct personality. The girl turns to the inner world of her imagination to deal with tragic events.

Tideland isn’t being shot in the USA, but in and around Regina, a city in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan, half way between Vancouver and Montreal. I arrive there on a crisp November morning. I feel an icy breeze, which Cullin later describes to me as “colder than an iron toilet mounted on the shadowy side of an iceberg.”

Gilliam hasn’t made a film in Canada before, and by this director’s standards, it’s a small picture. Taking a break from mutilating remains, he joins me. “Things are going surprisingly well, almost disturbingly well,” he boasts, not quite able to comprehend a production without the major problems that have hounded his moviemaking in the past. There is an agreeable atmosphere on set, in contrast to the gruesome happenings on screen. “The crew works hard,” he enthuses. “At the beginning, I was really irritated by their pleasantness. No matter how badly I behave towards them, they seem to bounce back with a sunny smile every morning. I’m not used to this.”

EVENTS haven’t always treated Gilliam so kindly: he has repeatedly had to suffer for his art. Since Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas in 1998, he spent years on projects that failed to appear. In 2000, actor injury, flash floods and low-flying NATO jets scuppered his long-cherished Quixote project. The unhappy events were pieced together in the hit documentary Lost in La Mancha, with Gilliam left distraught. He set to work on another project, Good Omens, based on the comic novel by Terry Pratchett and Neil Gaiman. But Hollywood was reluctant, in cautious post-9/11 times, to fund a film about the end of the world featuring the four horsemen of the apocalypse.

Meanwhile, Mitch Cullin sent his novel to the director. Cullin wasn’t attempting to sell it as a movie: he sought an appreciative note from Gilliam, or maybe a quote for the cover. He never expected Gilliam to respond by buying the film rights to the book. What attracted the director was its unpredictability: he was unable to determine where the story was taking him. Gilliam worked on the script with regular collaborator Tony Grisoni. But funds were not immediately forthcoming.

Frustrated in not getting any of his own projects going, Gilliam took on Brothers Grimm as a hired hand. Working in Prague, he attracted stars Matt Damon and Heath Ledger. Grimm is an enjoyable, strangely peculiar film, with stunning design and intelligent ideas. But problems were caused by interference from the studio Miramax’s Weinstein brothers. For example, Gilliam devised a look for Damon with a little bump on his hooter. “It transformed the actor,” maintains Gilliam, “but the Weinsteins said: put the nose on him, and we close the film down. And that was the night before the first day of shooting.”

The Tideland deal was secured while Gilliam was in dispute with the Weinsteins during Grimm postproduction. The Weinsteins wanted reshoots, so Gilliam abandoned Grimm for a while. “Rather than have a head-butting contest, which would have harmed Grimm, I did Tideland to let the air clear.”

AS I ARRIVE in Regina, all of the external work on Tideland is complete. The nearby Qu’Appelle Valley provided inspiration for Gilliam, and matched perfectly the tone he was trying to achieve. “The sky was beautiful. There are vast, exhilarating and liberating open spaces.”

It’s understandable for Gilliam to have an irrational fear of climate systems after his Quixote experience. Autumn shooting in central Canada presents the risk of a major snowfall, so the location work was scheduled first to avoid the wintry weather. For three weeks, the weather did all the right things, but the morning after the scheduled exteriors were finished, there were four inches of snow everywhere – supplying proof to Gilliam that there actually is a God. “Now we’ve completed our exteriors, and we’re safely ensconced in our soundstages,” explains the relieved director.

The director is happiest with the actors. “I can’t imagine this film without her – she is this film,” exclaims Gilliam, referring to a performance by wide-eyed Jodelle Ferland as Jeliza-Rose. “We had to hoist her up yesterday, and she was much heavier than a child her size should be. We suspect she’s actually a 35-year-old squished into a little body.” On set, the youngster practises constantly, she displays thoroughly professional behaviour, and also gives advice to cast and crew.

ON THE SECOND DAY of my visit, the crew moves to an even smaller set – the attic of Noah’s house. This closed, wooden set has just a tiny gap to allow everyone in and out. In this scene Jodelle is required to crawl through the attic and examine some boxes, talking to a doll’s head-friend, while holding a torch – which also acts as a light source. In each take, young Jodelle is extraordinary – delivering lines, handling props and performing complex moves that would challenge many established actors. Walking closely in front of her is Italian cinematographer Nicola Pecorini, using his Steadicam.

Before each take, a hands-on Gilliam works with cast and crew to solve problems. When camera rolls, he leaves the set and concentrates on his digital monitor displaying what is captured on film. I peer into the monitor and the attic is made to look enormous as a result of the wide-angle lens. There’s only one way in and out, it’s difficult to light, and there’s little room for Pecorini, which causes mistakes, changes and several retakes. “The sets were fine using mini-DV cameras, but when you put a proper camera in, there just isn’t the room,” complains the director.

Gilliam assures me it would have taken longer with sets that open and close. The lack of space and light is essential to Gilliam’s vision. “In contrast to the exteriors, the interiors are very dark, claustrophobic and irritating.” I wander into the attic when the shot is finished, to have a peek inside, and predictably I bang my head on the ceiling. I see the attic full of trunks, cobwebs, books, bricks and notice that a props joker has put Monty Python Live at Drury Lane at the front of an LP stack.

GILLIAM AND PECORINI worked together on Fear and Loathing. Yet the cinematographer was sacked by the Weinsteins several weeks into Grimm, against Gilliam’s wishes. “Nicola’s been working like a madman,” says the director. “We’re using some very odd angles to reflect the girl’s twisted journey. We’ve been freer, pushing it further than we normally would, because it’s a low budget, strange film. And I get bored…”

I witness the camera extremely close to the actors, with plenty of camera movement and tilting from side to side. Much is improvised – Pecorini confirms that the lens is chosen on the day. “There isn’t much choice, it’s always wide, wide, wide,” says Pecorini. “You always get the full set of lenses, but in the end we sent the long ones back. We’re saving 150 bucks a week!” Pecorini still hopes to shoot Quixote, saying it’s the best script he’s ever read.

FOLLOWING GILLIAM around is the Canadian director of Cube and Cypher, Vincenzo Natali, making a behind-the-scenes documentary. Natali is keen to debunk the myth that Gilliam, his hero, is a madman out of control. “Terry encourages that himself. He’s a performer who relishes being the mad artist – but in fact he’s a very pragmatic, logical thinker who knows exactly how to make a movie. He’d never do anything that would endanger it. It’s important for film producers to know that, they shouldn’t be afraid of Terry.”

Gilliam claims Jeremy Thomas, the film’s producer, is surprised that the director isn’t like his awkward-bugger reputation. This is the first time they’ve worked together, yet Thomas – with his similarly audacious track record, from Naked Lunch to Sexy Beast – could be the perfect match for Gilliam. Behind-the-scenes conflict has often provided inspiration for Gilliam’s work, but there’s none to be found here. This might be bad news for the documentary, but Natali jokes, “I try to push over a ladder, incite a fight now and then but it just doesn’t work! Frankly I’m more interested in watching him work, than seeing a film fall apart.”

On my final day on set, Jodelle and her doll’s-head pals are trying to locate a squirrel. At one point the camera is placed underneath a bed to capture a shot where an upside down girl and two of her friends peer down. Gilliam keeps the actress’s mood up by making squirrel noises and winding her up.

Later Jeff Bridges, who plays Noah, arrives in town to film the title sequence, where he and his band are to perform in a nightclub. However, Bridges is holed up in his room with back pain, consoling himself with vodka and cigars. There are echoes of Jean Rochefort’s injury which helped finish off Quixote. Anxious conversations take place, and I wonder whether Gilliam’s fortune on this picture is about to shatter.

CUT TO present day London, and Tideland is now complete. Enjoying a curry in Soho, Gilliam confirms that Bridges’s dodgy vertebrae didn’t halt the film. “Jeff was very nervous about that. For his rock’n’roll moment, we just had to pump him with some painkillers.” Gilliam reveals he identifies with Noah. “Life hasn’t worked out as good as it should. He’s angry, tired, and can’t communicate with family properly – I understand all that!” Bridges worked with Gilliam before, in 1990’s The Fisher King. Much trust clearly exists between director and star, given the alarming humiliations that Noah suffers in the film.

The finished film is beautiful, hypnotic and disturbing. At the very start, Jeliza-Rose prepares syringes for her parents. An unhealthy relationship develops between Dickens and Jeliza-Rose, with Gilliam thinking of them “as Quasimodo and Esmerelda”. A corpse farts. And the conclusion is explosive. Yet the film conveys its dark subject matter from the perspective of the innocent eyes of a child, and it is “neither salacious nor manipulative”, according to Gilliam.

The director concedes that there’s a point where viewers become impatient, because they don’t know where the film is going. “But people should relax and not try to push forward to the next bit of the story. We’re conditioned to narrative pace, which Hollywood is really good at. You need low bits for the other bits to really kick – so hopefully we’ve provided some low bits!” But there is always plenty for the eye to admire: decayed, brown interiors and beautiful yellow prairies, influenced by the paintings of Andrew Wyeth. There are some inventive fantasy sequences, including Jeliza-Rose falling down a rabbit hole, and of two doll’s-heads sewn inside a corpse, reminiscent of Gilliam’s Python animations.

TIDELAND has divided audiences in early screenings. “I’ve got a great response, but there are people who think it’s just terrible,” admits Gilliam. The director reveals that his Python colleague Michael Palin didn’t like it, “but when he woke up the next morning, he just couldn’t get it out of his head. He says it’s either the best or the worst thing I’ve ever done – but he doesn’t know!” Festival screenings have yielded both rave reviews and walkouts.

The appeal of Tideland isn’t mainstream enough to generate the box office business of Gilliam’s earlier Twelve Monkeys, but the director hopes that other filmmakers will follow his lead and deliver challenging material. “The world has become homogeneous, clean and nice. I’m relying on those with the nerve to be offensive and awful. Our film is different, and hopefully it’s not too alien. It’s just whether there’s a little girl inside of you!”