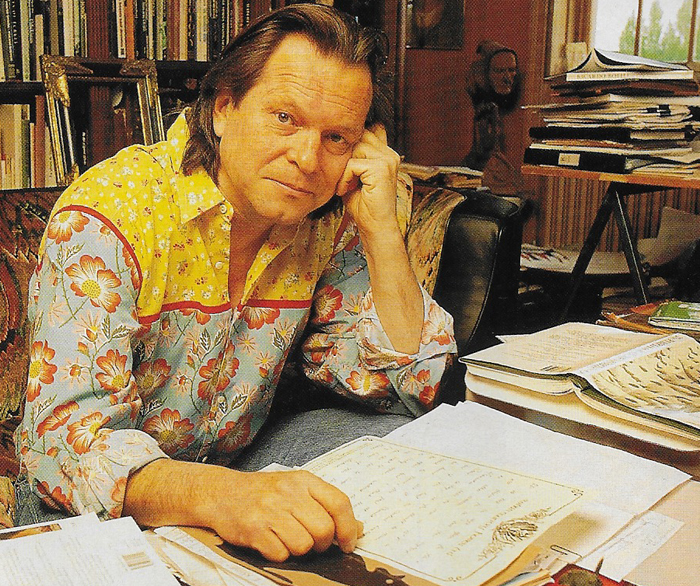

American-born Richard Lester came to the UK in 1955 as an experienced director of live TV. Following directing work in the UK for the recently-launched ITV network, Lester had a string of movie successes in the mid-Sixties. These included A Hard Day’s Night, Help, The Knack, and How I Won the War. Later in the Sixties 1968, he went back to the US to shoot Petulia, a fascinating picture set in San Francisco, featuring Julie Christie, George C Scott and Richard Chamberlain.

Lester has spoken extensively to Phil Stubbs about his life. In this excerpt, Lester discusses the appeal of the UK upon his arrival, and talks about the making of Petulia.

Phil Stubbs: You came to the UK in 1955 – what was the appeal of Britain?

Richard Lester: It’s terrible to go back so long – because they’re all the things that don’t exist now, such as individuals being respected, the quirkiness, and the unexpected. I found I delighted in being able to do, to be, to say, to think. There was no sense at that time of conformism as being essential. It wasn’t a country of three line whips as far as one could see. And when for example in 1956, Suez happened, people got on to their feet and walked to Australia House and Canada House and said, “That was a shoddy thing my country did, I’m leaving.” That doesn’t happen in America. You dare not do that.

Maybe because of my parents, or maybe because of myself, I have always despised emotionalism in every way. I despise jingoism, I despise patriotism. aside a small boy, I remember having the big maps of World War Two, and being totally involved and concerned in the success of that conflict. But from the time it was over, in a funny way, paralleling I suppose what happened here with Attlee and Churchill, I absolutely felt that there should be a better way and when the sniff of having a moderate socialist background and a non-religious background (I’m a devout atheist and coming from devoutly atheist parents) – it was easier for me to feel that I wasn’t isolated.

But again that implies that we were sitting around a great deal of time concentrating on this. This was just something that came up in conversation. When you’re in a jazz club and there’s Kenny Baker playing, Phil Seaman playing drums. Everybody comes in and you sit in and they’re nice to you and you have drinks with them. That’s what you’re thinking most of the time – isn’t Phil Seaman losing a lot of weight because he was a heroin addict going from a 14-stone drummer to an 8-stone drummer before your eyes. And incidentally, occasionally, you were saying “This Suez thing’s a shambles.”

When did you become a British citizen?

It was about 1990. For a while I thought it might be interesting, and not wholeheartedly for any political reason, to have an Irish passport. But we couldn’t pin down the date of my Irish grandfather’s birth, and without that there was nothing I could do. There were no records that ever existed in America. In fact I don’t have a birth certificate.

So I wasted about five years attempting to track that down otherwise I certainly think I would have done it before. Certainly by the time of Petulia, I felt I certainly wanted no serious connection with the USA, and my mother died the next year and that was more or less the end of it.

I felt I’d come to the end of the line of taking the Irish connection forwards. I thought, let’s do the next best thing. In 1962 I had declared domicile in the UK, which is a fairly comprehensive step. In fact it is more important than the passport because it’s a tax implication. My son was born in 1962 and the implication was I wanted him and any further children to be brought up in this country. I will be rested and domiciled, so that commitment came in 1962.

How did the Petulia project come about?

I was sent the script of something called Me and the Arch-Kook Petulia – written by a Los Angeles dentist – set in Los Angeles about a American girl and a doctor.

Who sent it to you?

It was sent to my manager by Raymond Wagner, a film producer.

Had he worked with you before?

No, he didn’t know me, and I didn’t know him.

And he was based in the States?

Yes. I read it and thought it was absolutely dire. I hated it, hated everything about it. It was supposed to star James Garner as the doctor. I can’t remember who the girl was going to be. There was a first draft screenplay, but it began to annoy me more and more, and I thought that people don’t behave like that, they don’t talk like that. I didn’t believe anything about it.

And I began to think more about what it was that was disturbing me. And I felt it was an opportunity to have a voyage of discovery. I’d been out of the USA for more than ten years, and I thought this might be very interesting. Vietnam was just really catching on, and I suppose the script came to me in about 1965. I thought very terrible things were going on, and maybe if I can do something very interesting – in essence looking for the first time in ten years at this society and maybe this was the kind of subject that could do it.

I thought that the girl should be English and we should switch it from Los Angeles with its interbred, overweening concern for cinema and Hollywood, and we took it up to San Francisco – which was very fortuitous because it was the beginning of the hippy movement. It hadn’t really started but there were rumblings going on there in 1965.

I got Charles Wood, whom I worked with on most of my films. He and I went to San Francisco and wandered around. Charles wrote this most amazing document based on the characters that were in the book, but really just a diary. It was written on the back pages of one of these Collins page diaries and scribbled. We’d go into bars and listen to people say things – we’d go to amusement adventures and then go into the parks and just pick things up and watch television at night, watch what was going on.

And then we thought that if he’s a doctor we should go into a hospital. Charles and I went into a hospital. We saw found out there were blank televisions. People came and said, well, I can’t get the television to work. Hospital staff said, well they’re dummies. Well, we thought, wait a minute it’s good, and so we eventually ended up with it in the movie.

I had to get rid of James Garner, whom I quite liked as an actor, but I felt wasn’t right, and then I had to fight to get cast. They refused to have Richard Chamberlain because he’d been a failure in all the films he’d been in, and they absolutely refused to have him.

You mean he’d been a box office failure?

He’d been successful as Dr Kildare in the television series, but he had made three or four films, and all of them had been failures in the box office. So Warner Brothers said no and then I finally said that if I don’t have him I’m going to have Andy Williams – the singer – and I think they thought, “This guy’s mad!” Then they said they wouldn’t pay him very much. In the end we got a lovely cast. Joseph Cotton was great to have, and I think George C. Scott remains the best actor I’ve ever worked with. Certainly the most perceptive and intuitively correct actor I’ve ever. I think he was just a wonder.

So that was 1966, which was when the hippy movement was still flowers, peace and happiness. We went back in 1967 to shoot, there were guys in three piece suits, driving their Mustangs in and then changing into the beads, putting the flower behind the hair. And the drugs scene had started to turn organised and ugly, and that’s when we were shooting. So we saw both sides of that… how a society, how a sort of dream, a little idea, a little pocket of Americanism, can turn so bad and was so corrupted so quickly. It was a very depressing time because in both that and coming back, because Petulia was the American entry to the Cannes Film Festival at the same time that the May riots happened. The festival ended early and we couldn’t get out. I was supposed to start shooting The Bed Sitting Room on the Monday. I couldn’t get out because there were no trains nor planes. The police were baton charging, and we had to try to get across to Italy and make our way through Europe in order for me to start work on the Monday morning.

So, if you like, Petulia and The Bed Sitting Room were my take on what it was like being in the firing line of two of the most extraordinary events of the century.

We went to the USA as a British crew. I had Nic Roeg as my cameraman. I had two camera operators, I had Antony Gibbs, an English editor. I had Tony Walton as production designer. I even got an interior decorator, David Hicks, from the UK to come over to do Petulia’s house. I wanted something that looked like it had never been lived in, or thought about by a person, but that it was a designer job – so I got a designer to come over and do that, so in essence it had a very English feel to it.

We made the film almost without half of crew. Warner Brothers were uncooperative. I used to grab a lot of shots secretly in the streets with hidden cameras. Warners insisted that every member of the crew wore a Warner Brothers baseball cap and a T-shirt as they went onto the street. I had to get signed a release form if I photographed anybody. I said, “That’s bollocks”.

I received memos from the sound department saying for example the sound on scene 42 shot 7 was unacceptable, so re-shoot. I just ignored them. As soon as the film was over, I took all the negatives and brought them back to London to cut it here. And then I said here it is, it’s finished. So I had thought I was going to complete the film over there, and that didn’t happen.

The flashforwards and the flashbacks within the film reminded me of Nic Roeg’s later work – do you think that it was an influence on him?

Definitely

Did he have any input into the structure of the film?

Not at all. Actually we helped Nic in what was going to be his first film Walkabout. It turned out to be his second film. My company bought the rights to it for him and I introduced him to Sidney Nolan the painter and Edward Bond who wrote the first draft screenplay. The flashbacks and flashforwards within Petulia were in Charles’s idea and they were carefully scripted. They were in the script long before Nic saw it. But there is no doubt that Nic was always very helpful.

In fact Nic helped me rewrite A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum while he was cameraman on that. I knew it needed major rewriting and the producer had written the screenplay and he wouldn’t let me have a writer – so Nic and I did it together. Nic had always been much more than just a cameraman. But the structure of Petulia was in every draft of the script.

In general, what have your experiences with Hollywood been like?

That’s all there’s been. I’ve dealt with a great number of projects, almost all of them have been supported by Hollywood money. I mean my first seven films were all either Columbia or United Artists but they were in the days when you were left alone. You told them what the budget was going to be, all the first eight films made money, and so they left you alone to do it. And there was no question of having screenings, or test viewings or showing the script to people and saying d’you think you’d like to see a scene like this. That didn’t exist in the Sixties, thank God, otherwise I wouldn’t be here talking to you.

Has anyone tried to persuade you make a film in recent years?

Nobody has come up with a realistically interesting idea. I probably would say no anyway. I feel as though my time has passed. I feel that there are lots of reasons why I would not be good at carrying on like the Bunuels and the Renoirs and the Bergmans. I just think that my way of working which is very much working on ones nerve and ones instinct requires an energy level that I did have, but no longer have. I could pull a crew of 140 around by personality of saying come over I’m bloody well going to do it. And I would never sit down in a chair, I would just keep going. First, I think my energy level is not strong enough. Second, I suspect like anything else I kept in my head what we were going to do and what I needed and if I’d come into the room, we’d do the long shot, I knew exactly in my mind what exactly we’d need to do to make this scene work and put the cuts together.

And you do get to a point – I don’t want to sound doddery – where you start going upstairs, and half way up you think, why am I going up here what am I going for? I think there’s that suspicion in my mind that I would finish, say that’s great we got it and then realise there were two inserts that I never really got that would be crucial and that I have never developed a way of working to either write them out in advance or trust other people to say you need a close up of that.

And also being electronic age, I used to know cameras, I used to know lenses I used to know I prided myself on understanding the difference between one film stock and another film stock and why it would be helpful to have this stock for this kind of light. All of that doesn’t exist anymore. It’s you computer bastards that have really destroyed it for me. Going in saying, if you want it green guv’, here it is, green. I don’t like that!